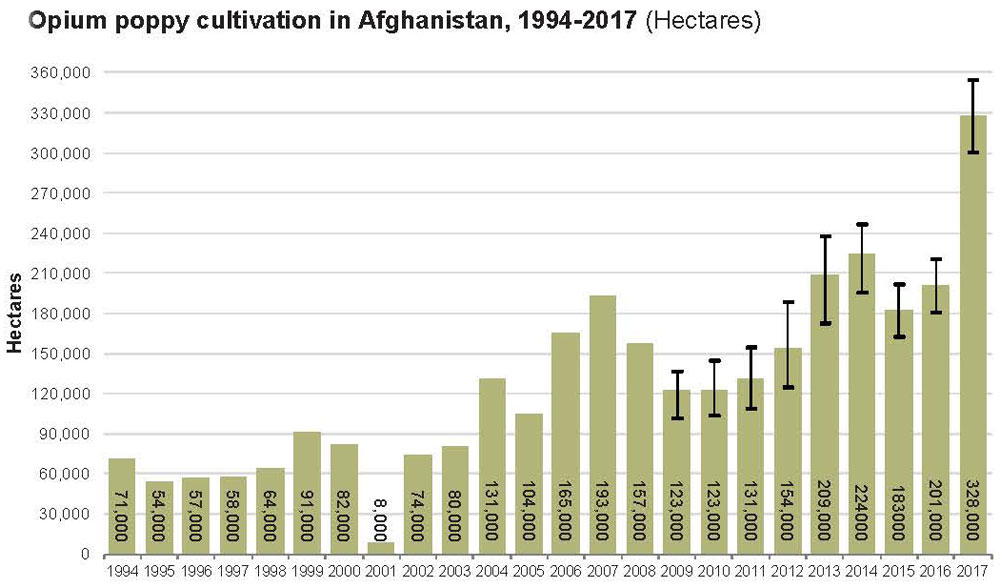

Afghanistan is the world’s largest producer of opium. In 2007, it was found that the country’s then opium harvest amounted to 8,200 tonnes and thus provided for 93 per cent of the world’s illicit heroin supply[1]. According to the US Department of State, 90 per cent of the heroin found in Canada and 85 per cent of it found in the UK is cultivated and can be traced back to Afghanistan[2]. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, as of 2017, Afghanistan’s opium poppy cultivation has increased from land covering 201,000 hectares in 2016 to 328,000 hectares in 2017[3]. This shows a set rise in the levels of cultivation of opium poppy in the nation-state. The reason the drug trade carried out in Afghanistan needs to be looked into is because it is funded and in turn, funds the Pakistan backed, Pashtun force, the Taliban. The Taliban has now turned into a drug cartel and Afghanistan can be termed the first true narco-state- “a country where illicit drugs dominate the economy, define political choices and determine the fate of foreign interventions”[4].

Opium is considered the ideal crop for a worn-torn region because it provides faster yields, little capital, and is easy to trade and transport. ‘Desperate times call for desperate measures’- this is what led the poor farmers to turn to opium for it yielded higher profits and could provide for the urgent need of food when the prices were continuously on the rise. Afghan farmer growing opium can be paid close to $163 for a kilo domestically, while after it is refined to heroin, it sells for $2,300-$3,500 in regional markets. In Europe, the same sells for $45,000 in wholesale, while the retail price is considered to be much higher[5].

The turn of the rural population to cultivating opium can be traced back to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in in 1979, and the subsequent intervention of the United States into the scenario. The CIA funded the mujahedeen with close to $3 billion to launch guerrilla war on the Soviets. The Afghan resistance was backed by these funds and an increasing opium harvest[6]. By 1984, Afghanistan supplied heroin made up 60 per cent of the US market and 80 per cent of the European market[7]. During the period of civil war in the nation-state, the only crop that ensured return was opium, and thus, various farmers chose to grow it. The opium fields also served as employment opportunities in times of war, for tending to the plant and harvesting it required more labour as opposed to the traditional crop of the region, wheat.

With the Taliban coming to power in 1996, there was a rise in opium cultivation for they encouraged it and offered government protection to export of the same. They also collected taxes on the cultivation of opium and on the manufacture of heroin, which funded the government. During the Taliban rule, Afghanistan accounted for 75 per cent of the world’s opium and heroin production[8].

The production of opium and heroin increased after the USA intervened again in Afghanistan in 2001 to curtail the Taliban insurgency[9]. Though the country was in economic and political ruin after the Taliban government was toppled, the pumping of money into Afghanistan saw a rise in opium cultivation. The USA took support of the Tajik population in the north of the country, which controlled the drug trade in the area, and of the war lords towards the east and south east. These were close to the Pakistan border, and another hub for drug smuggling[10]. Therefore, the ground for a major drug cartel set-up was already in place.

In the years to come, the profits made by the opium trade and drug smuggling, went to the warlords first, and then to the Taliban guerrillas. Yet, it was only in 2004 that there was a suggestion that the drug money was funding the Taliban, and thus refuelling their insurgency[11]. The Taliban was using the money to fund their arms, logistics and other requirements of the organisation[12].

Under the Obama Administration, the USA carried out counter narcotics operations in Afghanistan, especially in the Helmand province, which accounts for close to 80 per cent of Afghanistan’s opium poppy cultivation[13]. Yet, by eradicating the Taliban guerrillas and not the opium harvest, every spring there is a new crop of guerrilla fighters for their cause. This led to the Obama government ending all combat operations in Afghanistan and maintaining 8,400 troops in the region for only security purposes in 2016[14].

It is not only the Taliban which is profiting out of the drug trafficking, but also the provincial officers, especially in the Helmand province, which goes to say that the Afghan government is also making the most out of the high yields of opium.

The Taliban imposes a 10 per cent tax at every stage of opium trade, and is also looking to control more heroin laboratories so as to be able to refine opium within Afghanistan itself. Recent data suggests heroin trade makes up to 60 per cent of its revenue[15].

Over the decades, opium economy has got embedded in the socio-economic structure of Afghanistan and putting a complete ban on it will impoverish huge portions of the population. One of the ways to begin tackling this problem would be to use the government funds being put into Afghanistan to provide the farmers with food crop seeds, so that they are slowly able to move out of opium cultivation. Bringing change in a society is hard, but the only policy which can be followed in Afghanistan is that of persistence.

[1]Woody, C. (2017). Heroin is driving a sinister trend in Afghanistan. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.in/heroin-is-driving-a-sinister-trend-in-afghanistan/articleshow/61349081.cms

[2]Note 1.

[3]United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2018). Afghanistan Opium Report. UNODC Research. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Opium-survey-peace-security-web.pdf

[4]McCoy, A. (2018). How the heroin trade explains the US-UK failure in Afghanistan. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/jan/09/how-the-heroin-trade-explains-the-us-uk-failure-in-afghanistan

[5]Note 1.

[6]Note 4.

[7]Note 4.

[8]Note 4.

[9]Walters, J., & Murray, D. (2017). Kill All the Poppies. Retrieved from https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/11/22/kill-all-the-poppies-afghanistan-heroin-taliban/

[10]Note 4.

[11]Note 4.

[12]Note 9.

[13]Note 1.

[14]Note 4.

[15]Note 4.